Tim Hext: what the end of the Central Bank era means for investors

How will the journey from deflation to inflation impact portfolio construction, defensiveness and income in this zero-rate world?

On May 28, 2020, Pendal’s Head of Bond, Income and Defensive Strategies Vimal Gor and senior team members Tim Hext and Amy Xie Patrick outlined the implications for investors in their half-yearly “Lighthouse Series” live webinar.

This is a recording of Tim Hext’s presentation which addresses the end of the Central Bank era and what that means for investors.

Watch the video above or read the transcript below.

I’LL HIT the two key themes straight away, and then we can talk more about them.

The first one is that we are at the end of an era. And I’m calling it the era of the central bank. Central banks, as we all know and are now tapped out.

Rates are at zero. And from this, a new economic framework will emerge. Really we’re entering the era of fiscal policy.

The second thing I’ll be talking about is the fact that, of course, under that year of fiscal policy, it’s government, not central banks who need to step up.

My concerns, which I’ll talk a bit about, are the fact that I don’t think all governments are going to be in the mindset that we are in this new era.

And that some of the conventional thinking is going to slip back in as we come out of this immediate crisis. And what that will mean potentially a double-dip recession next year.

So let’s move on to what I’m calling the cult of the central bank.

Now cult might seem a strong word. I doubt we all worshipped our central bankers, but certainly for people like myself, we’ve been in markets for around 30 years, we’ve lived in an era where central banks have been front and centre of everything.

Now I’ve putting a picture of two US central bankers up there. I think Alan Greenspan loved the fact that he wants the high priest of the central banks.

I spent many an early morning trying to decipher what the hell he was saying.

So he certainly pushed that idea. I think Bernanke who ended up being sort of Superman through the GFC and saving the US economy, I put a quote showing he’s a little bit more circumspect about the role of the central bank.

But there is no doubt for all of our careers and I’m not just talking about our careers in markets, but the economic framework we’ve operated under, has the central banks front and centre. To sum it up in one line, the government outsourced cyclical control to central banks.

End of an era

The era of course is now over. It’s just a fact when you’re at zero rates, your arsenal of things you can do becomes very limited.

And there are a few little things they can do, but in terms of shifting the dial significantly, they are out of the game.

So it’s the end of an era. It’s an era from which we’re about to emerge, and we need to consider what the new framework looks like.

I’m just going to quickly recap what happened during that era, because it gives us a good understanding.

So the golden age of central banks, if you like was from ’93 to ’07. I use ’93 in Australia because that’s when inflation targeting came in.

Of course it came in slightly earlier in other countries, particularly New Zealand. Now under this era, fiscal policy was basically resigned to trying to balance the budget through the cycle.

Of course it would go up and down as the economy went up and down.

For the federal government, the two main things of course are taxation and welfare spending. So you would get surpluses and deficits.

But the aim of fiscal policy under this narrative was it should try and balance things through the cycle.

And it was left the monetary policy to be the accelerator and the brake under which we operated.

We had a nice framework targeting inflation and full employment.

And from that came all sorts of other ideas, which we sort of took as second nature and we started to believe were sort of almost like a natural order.

So there’s two concepts.

One was NAIRU, of course, where unemployment starts to become inflationary.

And the other idea was the idea of a neutral rate and I even heard people talk about it over the last 10 or 20 years as the natural rate of inflation.

And I think that speaks to the fact, a lot of people thought we’d finally landed on a framework, which somehow was a natural framework, that the economy was a bit like science.

It had rules that followed and here we had finally uncovered the magic on how to make it work for us.

Of course there was very good economic management through that period from central banks. They didn’t get everything right, but largely they did.

Two tailwinds

But what people only now really looking back realise is just how significant two tailwinds were.

The first was they were operating under very positive demographics.

We all know this story, that through the ’90s and into the Noughties, there was a massive increase in the percentage of the working age population.

Supply and economy was expanding and you could expand it under those circumstances. The second tailwind of course was globalisation, which was a massive move towards goods price deflation, which offset what you were seeing elsewhere. And you put those two together. And it was really the golden age.

As I mentioned, GDP in Australia, averaged 3.75 per cent through this period, inflation almost spot on the 2.5 per cent target, and I think everyone agrees it was a success.

And then of course it wasn’t. The GFC hit.

Now the GFC in a sense should have put some serious dents.

But two things happened. Firstly, fortunately for central banks rates were high enough that they could do massive interest rate cuts to help the economy in Australia.

It was almost 4 per cent worth of cuts.

The second thing, more offshore than in Australia, was the emergence of QE [Quantitative Easing].

The two of them together as we emerged from the GFC appeared to have solved the crisis.

So we entered the next era from ’07 to 2010 where the cult of the central bank in fact was strengthened, not loosened by the crisis.

It looked like they had saved the day. So as we entered this decade, we just finished, central banks were very much again front and centre.

But then the cracks started to appear. Not for a while, but they slowly started ekeing out here in the last decade.

We all know this story, but it’s just good to recap it. For a while there it looked like things were returning to the pre-GFC normal. That we could target growth about 3% and inflation at 2.5%.

What we found as the decade went on, of course, is that we just weren’t hitting those targets consistently.

And despite interest rate cuts, we just weren’t getting there. Fiscal policy should have been balancing. Unemployment was going down.

Yet we seem to have almost structural deficits.

Monetary policy, even though, there were numerous rate cuts through this period, inflation was going down, not up. But, and here’s the important part, the narrative was still held by everyone, including importantly to central banks. In Australia, the Reserve Bank kept forecasting that we were going to get back to these levels.

It was just going to take maybe a year or two years.

But right through this period their forecast always had inflation going back to 2.5% and GDP above 3%.

Of course, what followed were consistent downgrades.

So what started to happen in the second part of the last decade was a few question marks appearing.

Was there something structural coming on and you heard Phil Lowe talk about this.

Was it technology? Was it changes in the workforce that were causing these moves to happen? No one was quite sure. But what we started to see was the realisation that what was going on is far more structural than cyclical.

Now we’ve been going down this path for a long time and all the recent crisis has really done is accelerate it.

I wouldn’t say it’s the crisis we had to have because it did come completely out of the blue.

But in a sense it revealed these cracks, made them wider, and made the whole system come under severe pressure.

So there is no doubt that we need a new economic model.

Conventional monetary policy is exhausted.

Negative rates may be tried in some places. I think the Reserve Bank’s attitude in Australia is they don’t work.

They do more harm than good.

End of conventional monetary policy

So conventional monetary policy is over. Unconventional monetary policy – well, that’s here to stay.

There’s certainly a lot more they can do. You can expand yield control, you can do a larger QE. But really they are playing around the edges.

Remember the aim of unconventional monetary policy is just to bring term rates down because you can’t necessarily control them without directly controlling them towards zero. And that may yet happen, but that’s quite limited.

It’s not going to save the day. It’s not going to really move the dial a lot.

So we are left with fiscal policy. Now we should, in a sense, be comfortable with that.

We should go ‘well, the government has a lot of power’. Because remember the government, the federal government I’m talking about here, has something that no individual company or even State government has, and that’s the ability to create money.

So they should use that super power that we’ve given them to really help the economy when it’s needed.

But here’s the problem.

Conventional economics has created a strong narrative that debt and deficits are bad things. It’s a narrative which is very hard to shift.

And it’s a narrative which I grew up with studying economics in the 1980s. And there’s a narrative that it’s been reinforced constantly since.

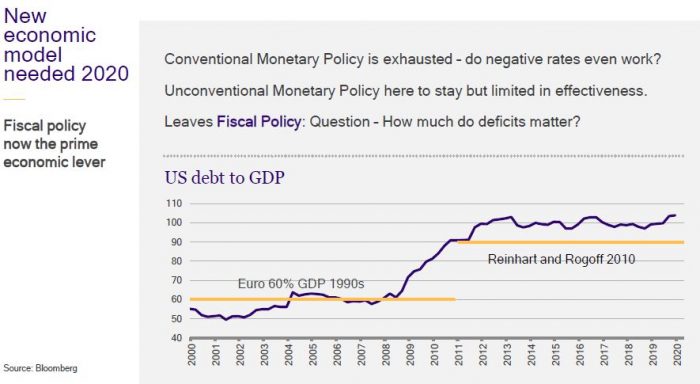

So the minute you start running high deficits, of course, all the worry starts to come out from this group of people and conventional thinking. So back in the ’90s the magic number of debt to GDP, and I’ve put the US debt to GDP here, was 60%.

That’s what you needed to get into Euro.

If you flash forward to the GFC, we had famous papers like Reinhart and Rogoff who told us that if we went through 90%, that you were going to severely impact the economy.

And of course the US has since sailed through that. And that hasn’t happened.

The poster child, of course, Japan, has got a lot higher than this and they are still functioning well.

So you’re going to get this happening in the next few months, and indeed the next few years.

You’re going to get that group of conventional-thinking economists talking about why this is all heading towards doom and disaster. The terms they’ll use I’ve even heard used in the last month by the prime minister himself.

Terms like: how are we going to pay for this? We’re going to burden our children with this debt.

And they really talk about the government as though it’s like a household or something else, which has to sort of live within its means, otherwise people stop giving it money.

The government doesn’t need people to give it money. It creates the money itself.

As Vimal will mentioned, done a whole paper on this so I won’t go into too many details.

So the new economic model where fiscal policy is at the centre, needs new economic thinking, if it’s to be used properly. And unfortunately, a lot of the economic thinking we have is still found in times gone by.

This concern about debt and deficits. Of course, we’ve seen the national debt clock in the US, the Tea Party jumped on the back of that.

And they were very vocal for a long time there, coming out of the GFC, that apparently the government being active and running deficits was going to cause all sorts of problems. Well they’ve gone quiet.

Of course, Tony Abbott has since left the building down in Canberra. Although I fear the ghosts of Tony Abbott still lurk around the corridors, but of course when he got elected in 2013, one of his big slogans was to end wasteful spending and pay back Labor’s debt.

The myth of government surplus

So the myth, I say, is that a government surplus is good policy.

Now don’t get me wrong. It would be great if the government could run a surplus, but a budget surplus should be the result of a strong economy.

It should not be an end in itself. And the fact that last year, as recently as last year, the government was trying to run a surplus, despite a lot of excess capacity in the economy, is just plain ridiculous.

And it’s not just me saying that. I think even Phil Lowe was down in Canberra, voicing similar sentiments.

Now you’ve got to remember the flip side of a budget surplus is a private sector deficit.

A budget surplus means a government is taking more money out of the economy than it’s putting in. You only really want to drain money from the economy if the economy has an inflation problem.

And you only get that inflation problem, if the economy is at or close to full capacity. I think we can all agree it’s a long way from there at the moment.

So what is a budget deficit?

The word deficit sounds terrible, but really a budget deficit is you’re putting more money into the economy then you’re taking out. You’re actually creating a private sector surplus.

And more importantly, you’re creating activity in the private sector, which should see it come back. So it’s entirely appropriate.

You should be running deficits. And in fact, I would argue a budget deficit should almost be the natural state of things when you have the ability to print money. We can come back to that in a minute.

The myth of inflation

So just moving on, the second myth I think I’m hearing a lot more of in the last couple of months after this dramatic escalation in the budget deficit, is that the government printing money directly creates inflation.

It’s the idea that as the government puts all this money in, as the Reserve Bank does QE, all this money enters the system and creates inflation as more money chases goods.

An important thing to remember here, and this is a topic for a whole other presentation, but a couple of key points just for now.

Firstly, the private sector always nets to zero in the money system.

If you think about it, every dollar that we borrow comes from someone else. Every dollar we spend goes to someone else.

The private sector system always nets to zero. So if a government creates extra cash or drains extra cash, it has to do the opposite to offset it.

Now, normally running a budget deficit, what the offset is, of course, is the government then borrows that money back from the private sector, via the AOFM.

But it can choose to do another thing. And we’ve seen this in the last few months. It can choose to actually have the Reserve Bank create the money itself and the money therefore comes back by excess reserves.

Now it’s quite technical, but for those who follow these things, those excess reserves have gone up

considerably. But here’s the important point.

The government printing money does not directly create inflation. Only the private sector who does credit creation can do that.

And we saw that 15 years ago at the peak of the last boom, when we had a massive investment boom.

The private sector was running double digit credit creation. And therefore we got 3% to 4% inflation.

At the time the government was actually draining money via a surplus.

So the only way the government influences is by creating activity, which therefore creates confidence in the economy, which therefore creates investment in the economy, which therefore creates a lot more broad money.

And therefore we can start getting inflation back to where it should be.

So again, entirely appropriate for deficits to be run and if needs be for the Reserve Bank themselves to create that money.

As, as I mentioned, please look at my paper. If you don’t have it, ask for it. It’s a much better explanation that I’ve just given you there.

A new model emerging

So what is the new model that’s emerging?

As I said, monetary policy is basically dead. Now it hurts me to say this.

As I mentioned, I’ve made a whole career out of watching all the movements coming out of Martin Place and Washington and other central banks. We’ve hung on their every word. We’ve lived and breathed everything they’re doing.

And as an investment manager it’s been front and centre of our decision making.

But they’re out of the game effectively. They’re now spectators.

Sure, they’ve got still an important part to play in liquidity and if the crisis were to worsen again. I think the job they did in March and April was excellent.

And they’re still there to do that. But they are not there anymore to create inflation. Only the government can do that.

Now what concerns me, is does the government fully realise this?

The government, of course, again has done a great job in this crisis. A crisis like the GFC brings out this

side of government that they have to act.

They have to do something and suddenly they’re not scared of deficits.

But you can see as we emerge, we’re already seeing this creep back to the old way of thinking.

Not just at a federal level, but at a State level.

People are talking about, wow we have to have budget repair to claw back all this money

we spent. That is not the case.

And if that thinking comes in it virtually guarantees a double dip recession.

Now the themes under this new model, (Amy, as mentioned, will be talking about these), clearly

“carry and roll” are your strong friends.

Income is something, investment grade’s got an important part to play.

Inflation

And of course you can look at yield enhancements. Now for the last part, I’m going to talk about inflation because it’s a question I get asked a lot.

Really with short rates stuck at zero for the next five or maybe even 10 years, the long end will be buffeted around by what’s going on in inflation.

Clearly, the COVID-19 crisis has thrown the whole thing up in the air.

What we’ve seen over the last decade was a lot of merge towards that 2%. It was very little dispersion between various parts of the CPI basket.

Everything seems to go around there.

What we’re going to see now is a lot of dispersion between various factors.

Some will actually be stronger than they were pre the crisis, but a lot will be considerably weaker.

Inflation catalysts

So what are some of the upside catalysts to inflation that we’re thinking about in our framework? The first two, trade disruptions and supply chain reorganisation, would probably go under the theme of the peak of globalisation.

We are seeing some unwind.

Again, that was already happening through the crisis, but the crisis has dramatically escalated that.

Now it’s fairly obvious that if you’re going to source a lot more locally and you’re going to lose some of that benefits of globalisation or specialisation as we were taught back at university.

You will see some inflation emerge in certain product areas. That’s a given.

The second thing, which is actually pro inflation is the cyclical rebound won’t be weighed down by the same de-leveraging we saw after the GFC, particularly in Australia.

Maybe in the US less so. But the third one’s going to be very interesting.

There are certain sectors of the economy where we’ve got to suffer structural supply shocks from this

crisis.

In other words, certain things just won’t be coming back. A lot of marginal businesses will be closed forever. You can even see things like Target stores recently. You can see things like Virgin Airlines. If it were to come back, talk about being a lot smaller scale.

You are going to see some areas where as demand returns it’ll be pushing up against a much lower supply and you will see inflation in certain sectors.

However, those sectors as part of the CPI basket overall are not that high.

Which turns us to what the deflationary factors are.

Unemployment

The first one is obvious across the economy. High unemployment means zero wage growth.

Even the RBA themselves don’t have unemployment coming back anywhere near what’s needed for the next three or four years.

Slowing population growth

The second one is a new one, and this is the first time we’ve faced this in decades.

The population not growing.

Now it is temporary. But it is temporary for at least 12 or 18 months. We’ve seen a lot spoken about this recently.

This has big implications for housing particularly. Not so much house prices, which will be partially

saved by zero rates, but in the areas which actually feed into the CPI basket of rents and building costs.

Now rents, building costs, together with with utilities and rates make up almost a quarter of the CPI basket.

And we’re going to see rents and building costs go negative over the next 12 months.

In the case of rents, perhaps significantly negative. And they’re a huge part of what’s going on.

I actually had a different view the end of last year. I thought we’re starting to signs of a recovery, but it is a massive shift when you go from immigration of the levels we have seen down to zero.

In fact the population will only probably be positive by natural bursts in the next 12 months. That, as I said, will eventually come back, but it is years away.

Government-led zero inflation

The third one though, which really has me concerned, is what I call government-led zero inflation.

This is a version of the paradox of thrift, where all of us save, it might be in our own interest to save, but if all of us keep saving, the economy goes backwards.

Now this is a similar thing with inflation. A lot of government policies during the crisis and emerging from the crisis, all look good in their own right.

For example, the NSW government announced a wage freeze for public servants this last week for the next 12 months.

Now on the surface, that might look good. You might think that the private sector has got no wage growth, it’s the responsible thing to do.

Their budgets have been hit. They need to pull back spending. The trouble is as that thinking seeps into more and more areas, it starts to become self-fulfilling that you get zero inflation.

You can even look at things like the free childcare, which of course is going to cause a negative inflation print for this quarter, but will the government decide to keep that going long or maybe decide to keep some sort of subsidy in place above and beyond the crisis?

No matter where you turn governments seem to be adopting a policy that no growth in rates – and remember we’ve had a healthcare charge freeze as well – there’s going to be a lot of things that used to tick over at 2%, 3% or 4%, are now going to be at 0% possibly for years to come.

This will lock in that zero-rate inflation rate environment and be a big factor.

And it worries me that this thinking seems to be creeping in more and more. Particularly at the federal level

where they should be doing the opposite.

They should be trying to create activity.

Credit creation

Finally sluggish credit creation. There’s hardly an earnings call that goes by, where rather than mention the great opportunity this crisis provides to buy more businesses, people talk about having to shelve investment plans to repair the balance sheets.

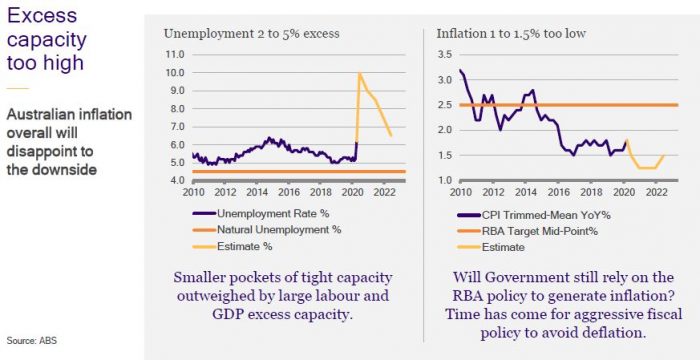

All of these things together mean that we very much land on the side of inflation is going to be a problem to the downside. Excess capacity, quite simply is too high.

As you can see here – unemployment. This yellow line is the RBA’s forecast.

You could argue 4.5% for NAIRU was too high anyway. We’re not going to get within cooee of that. So we have a major problem.

And finally inflation, as you can see there has very little chance of getting – this is underlying inflation, not headline – headline will be negative.

Underlying inflation has very little opportunity.

So what we call upon in a sense, and the conclusion I make is that unless we get a rethinking of the framework by the federal government, unless we start to see them truly step up and use fiscal policy to avert the crisis that the RBA previously would have averted, then we’re going to head for a double dip recession, and we’re going to head towards zero inflation.

I hope they wake up to that, but for a fiscally conservative party, it’s going to be a difficult road to trade. So I’ll leave it there now and I’m going to pass on to Amy to talk about how we’re looking at fixed income investing in a zero rate environment. Thank you for your time.

Tim Hext is a portfolio manger with Pendal’s Bond, Income & Defensive Strategies team.

Tim joined Pendal Group in February 2017 with responsibility for managing Australian Bond portfolios. Tim has extensive experience in banking, financial markets and funding.

Pendal is an independent, global investment management business focused on delivering superior investment returns for our clients through active management.

Find out more about our investment capabilities:

https://www.pendalgroup.com/about/investment-capabilities