Vimal Gor: how low rates and deflation will impact investors

How will deflation impact investors in a low-rate environment?

Pendal’s Head of Bond, Income and Defensive Strategies Vimal Gor (pictured above) explains in this plain language keynote presentation from the Conexus Fiduciary Investors Symposium on May 19, 2020.

TODAY I want to run through some of the unprecedented numbers we’re seeing and outline how this economic environment could play out.

What is the economic outlook?

Let’s put the current situation in perspective. Take the non-farm payrolls number (see below). This graph, which goes back to 1940, puts into context how monumental this slowdown has been.

It’s becoming more of a consensus view that the size of the lockdown — and the commensurate policies that have come with it — have largely been the wrong ones.

We arguably shouldn’t have stopped the economies as quickly as we did. We should have followed a different model and now we’re trying to pull ourselves out of this massive economic contraction we are experiencing.

There is no getting away from the fact that this is a massive shock.

Shocks historically have started in the financial system, for example the dot-com and GFC crises. This one started as a health crisis which flowed into economics then through to financial assets. So it’s a very different beast than the crises we have seen before.

That is why the authorities have had so much trouble dealing with it.

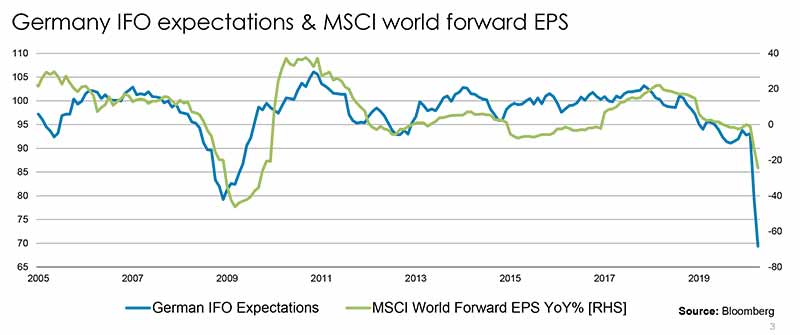

This chart below shows Germany, but I could have used pretty much any country.

I’ve used the IFO expectations which is a PMI and I’ve just put it up against MSCI world for EPS. We can see how the situation is going to get worse before it gets better.

Global data is awful. The April US retail sales number was down 16% — which puts it down about 30% since February (excluding food).

It is quite clear many businesses will not survive this crisis. High-end restaurants run with a margin of around 5% to 8% and they’re going to be running at 10% to 30% capacity.

Yes, we have dealt with the liquidity issue but we’ve got a solvency issue which is going to come up and hit us later. Do we have enough firepower to deal with that?

We’re going to see a tsunami of bankruptcies — there’s no other way to think about this.

The reason we’re not seeing these bankruptcies already is the government lockdowns and life-support mechanisms are delaying the process.

We can see here that earnings are going to be terrible. But we know the S&P is down only marginally from the levels we came into the year — so what’s happening?

It’s about multiple expansion. P/E multiples expanded on the back of liquidity, but earnings have been decimated — and it’s very clear earnings are going to get hit further.

Central banks responded very quickly. They did the usual: conventional monetary policy, cutting rates to zero. This was followed by unconventional monetary policy, yield curve control and more quantitative easing at a size we’ve never seen before.

Quantitative easing in the US is five times the size of all the quantitative easing we’ve seen in the last 10 years put together — unbelievably large.

The Fed and other central banks then started going into the fiscal policy area — somewhere they’ve not normally gone before.

They start supporting the markets and the economy directly, bypassing the banking system.

The Fed and central banks around the world have thrown every measure they possibly can to get rates down and flood the system with liquidity.

It’s my strong belief they will have to take rates negative. They don’t want to take rates negative — Powell talked about that last week about the fact that they don’t want to do it.

We know operationally the US isn’t ready yet and there is very strong resistance from the lobby groups and the banks.

But when nominal interest rates are 50 basis points in the US and you’re going to get a big wave of deflation, you’ll have real interest rates rising — which is just going to crunch the US economy further.

So, we believe the only material thing the Fed will be able to do is cut rates to negative with a short, sharp shock the way Kenneth Rogoff has recommended.

They clearly don’t want to. But I think there’s no choice — which would mean bond yields across the world would go negative as well.

What are defensive assets today?

While yields are already low, you can very clearly own 10-year Treasuries until they’re at -1%. I think they’ve got a lot of juice left in these markets. People don’t want to be owning them here but they should be.

The more bonds rally, and the lower yields go, the more people will need to buy them.

The Fed has done everything — conventional monetary, unconventional monetary and now they’re doing fiscal policy.

This chart shows investment grade spreads relative to non-manufacturing PMIs:

You can see we’d be off the scale if the Fed wasn’t artificially supporting credit spreads — we’d be at 600 to 700 given the non-manufacturing PMI.

The slowdown in the economy should lead to much wider spreads — but it hasn’t because of the backstopping by the Fed.

Not only is the Fed backstopping investment grade corporates via ETFs, they’re now doing high-yield fallen angels.

They’re effectively doing everything they possibly can to stop the markets dislocating and to plug this hole. But what they’re doing is plugging a solvency hole with liquidity, and ultimately it will fail.

We know the size of the central bank response has been massive, but then we had this coupled with the response by the governments as well.

This chart below shows the change in cyclically adjusted primary fiscal balance, this measure will give you an idea of how big the government fiscal response has been.

You need to think about this in terms of the US.

I’ll put it in perspective in terms of the US.

We came into this crisis with a fiscal deficit around 5% in the US. That’s ridiculously large on the back of the longest expansion in history. Plus we’re at full employment.

We came into COVID in the worst situation. We had very high debt levels in both government and corporate debt, and investors had portfolios which were pushed out the risk curve as they stretched for yield

So the virus hit us at exactly the wrong time.

Coming into this crisis the US was running a 5% fiscal deficit, we’ve now had support packages in the region of 15%. The economy has slowed dramatically which will lead to a drop in tax revenue of about 3% to 5%.

Nominal GDP is also going to detract about 5% over the calendar year, so we’re looking in the US for a fiscal deficit somewhere 20% and 25% of GDP.

This next chart shows you how unsustainable this is. The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates below show numbers back to 1790.

There’s zero chance they’re going to be able to pay this money back. Zero chance.

So how will they close the hole?

They have to defaults — either implicit default through inflation (the preferred course of every central bank and government in the world) or explicit default (restructuring, tax rises and spending cuts).

We talk about rebuilding the budget in Australia and trying to pull things back.

But there is zero chance across the world this money’s being paid back, so we need to engineer inflation or we need to do some type of debt jubilee, or a combination of the two.

The outlook for inflation

Lots of things drive inflation over the long run.

Factors that have kept inflation down over the last 30 years include the three Ts — trade, tech companies and titans.

Up until recently we had free and growing trade; we’ve had the influence of the tech companies (eg Amazon and its pricing power and ability to push prices down); and the titans (the rise of massive companies with oligopolistic or monopoly positions).

You’ve also had the two Ds — debts and demographics.

All these factors have been weighing on inflation. It’s quite clear here in the next chart showing M2 minus real GDP — but you can put any measure of money supply for any country in the world and the US is the poster child for this.

Money supply is absolutely ballooning.

Initially, the run-up in the money supply was unexpected as corporates drew on their revolving lines of credit.

That increased money supply as the banks were forced to lend to them. Then the Fed began pumping money in the system.

The three-month change in M2 in the US shows it is running at over 100%.

These are numbers you couldn’t even imagine. At some point that will start feeding through to inflation.

When you think of Irving Fisher’s theory of money, on one side you’ve got money supply and on the other side you’ve got velocity. Multiplying the two together gives you nominal GDP.

But the velocity of money’s been falling since 2006-07 because the economy’s been slowing, nominal GDP is coming down and nominal interest rates have been falling.

Now it’s been falling off a cliff because there are no transactions happening in the economy.

The government’s trying its best to slow down the velocity of money by throwing all of these fiscal packages at it. At some point, whether it’s six months or a year when we start coming through this, we’ll see velocity of money stop falling and then probably start rising.

That means you’ve got this massive money supply up against the velocity which isn’t falling. That has to lead to higher nominal GDP and nominal inflation.

There is no question in my mind that we will be hitting an inflationary episode in the US over the coming medium-term — one to three years out.

I think that’s what the governments want. They want to deflate the debt away.

Even before the virus, the Fed told us they wanted to move to average inflation targeting — running inflation above the target to get the 15-year average up.

Now they might have to run this at 3% to 5% — so you’re talking some quite big numbers. The problem is we’re going to hit deflation first, then inflation after.

In the long run you get these structural forces — monetary policy, fiscal policy, demographics, debt, trade, etc — which influence a long-term inflation rate.

In the short run inflation is largely driven by the business cycle. It’s quite clear we’re going to hit GDP growth of minus -5% in the US this year, which will give you a deflationary environment.

The thing that really worries me in the US is the fact that shelter inflation — the part of inflation that has been holding up the inflation rate in the US — is now flat and starting to fall.

Excluding shelter, the CPI number we saw last week was 0.6% and this is falling rapidly.

So we’re going into a deflation episode in the US. I think the Fed has to counter that with negative interest rates.

Then when we start coming back to work and hopefully get a vaccine, that point is going to be super inflationary because I cannot see an environment where the central banks of the world pull back monetary policy anywhere near the pace they need to.

It’s quite clear they and the governments have over-delivered. They’ve filled a solvency issue with massive short-term liquidity.

When we talk about the deflation-inflation picture we can’t forget about the US Dollar’s role as the reserve currency. They call it the exorbitant privilege.

This shows you what that privilege is worth. You can see on this next chart as currencies weaken you tend to see bond yields fall.

The US can get bond yields falling while the currency strengthens and that’s a massive advantage.

The world certainly doesn’t like that advantage. China, Russia and Europe don’t like it. There will be a move away from the dollar standard at some point — it’s just a question of how long it takes.

I think that will go hand in hand with some kind of debt jubilee over the medium term and some greater role for crypto currencies.

The focus of the crypto world is Bitcoin for me. You can like it and not be part of the shiny hat brigade. All you have to do is accept the fact that crypto is going to be a much greater part of the financial markets going forward.

Most of the world’s central banks are currently working on crypto and some kind of stable coin right now. These are the equivalent of IMF SDRs — there is no doubt it will become more mainstream.

American billionaire Paul Tudor Jones had a note out just a couple of weeks ago expounding the benefits of Bitcoin. Literally, it’s the only tradable asset in the world where there’s a known fixed maximum supply.

You’re buying it because you don’t trust in central banks and governments. You’re buying it because they can’t deflate its value away — they can’t devalue your Bitcoin.

Whether you like Bitcoin as a construct or not, I think you have to accept the fact that the world is moving away from allowing the US to be the reserve currency.

We’re moving to a new regime. How we move away from a US reserve currency and how crypto impacts the long-term inflation-deflation dynamics have yet to be determined, but they will be material.

Vimal Gor leads Pendal’s Bond, Income and Defensive Strategies team.

Find out more about Pendal’s investment capabilities.